A conversation with Manfred Schmid

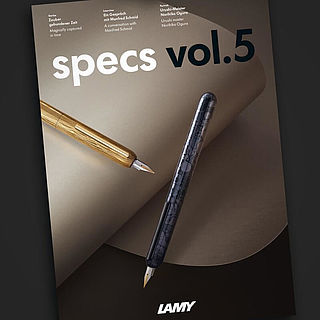

Manfred Schmid is one of the few urushi masters in Europe to have mastered this art form. He has created three of the four seasons for the LAMY dialog urushi edition: spring, autumn and winter. A visit to his studio in Bremen.

Mr Schmid, the art of urushi lacquering is rooted in the culture of East Asia and is closely linked with its virtues and traditions. How did you come to be involved with urushi as a ‘northerner’ from Germany?

Manfred Schmid: The Japanese say: you don’t come to urushi, urushi comes to you. I am actually a cabinetmaker by profession. I design and build furniture. In 1998, I moved to Barcelona and by chance discovered that you can study urushi or Japanese lacquering at the university there. Initially I didn’t want to do it professionally. I believe that if I had known how much effort it involves and that it can sometimes take one to two years to complete items in the black lacquer, depending on their size and the technique used, I would have run a mile! I am actually a very impatient person.

But you didn’t run a mile – quite the opposite. Since then, you have spent over 20 years dedicated to the art of urushi. What do you find so fascinating about it?

MS: My fascination with urushi began with the black lacquer. It is the deepest black which can be produced anywhere in the world. And the only black which is not produced with pigments. This makes the lacquer translucent – and the more layers I apply to an object, the greater the light refraction and so the deeper the black appears. It’s almost like looking into the surface. This is hugely fascinating, especially for people who have never encountered urushi before. Many of them find it irritating at first: it’s not glass, it’s not ceramic; so what is it? But they are immediately drawn in by its depth which emergesall the more, the less light there is. Japanese lacquering is actually, as the Japanese say, darkness deposited in layers.

Urushi is not just a form of craftsmanship; it also places great demands on the urushi master as a person. Working with the material requires a high level of discipline and great patience. As an impatient person – how do you cope with that?

MS: For me, it has to do with Zen and increasingly detaching yourself. You cannot dominate urushi. It is an unbelievably characterful material and you have to listen to it a bit. You have to place any rational logic to one side – like a musician who learns the technique at the start, clearly and rationally. But then if he wants to play well, he has to forget it all again at some point. Urushi is like that too. The more I say “Right, that’s it” when I get to the last layer, the less likely it is. Sometimes I do the last layer and then go home feeling dissatisfied. And when I come back the next day and start with the grinding, I discover: it’s really great, that’s it. Sometimes it’s rather paradoxical. But it has a great deal to do with entering a kind of meditative state.

My fascination with urushi began with the black lacquer. It is the deepest black which can be produced anywhere in the world.

Manfred Schmid at his studio in Bremen.

So to a certain extent, you have to let go?

MS: Yes, you could say so. When I apply the urushi lacquer, I cannot see with the naked eye whether or not the layer is even. I have to develop a feel for it and stroke the surface repeatedly. And at some point, this feeling becomes intuition. It’s like a cellist who can play an E without looking – it’s simply practice, practice, practice. Until at some point it’s like second nature. It’s the same with the grinding: I hear and feel more where I have been. It’s like penetrating the surface which I envisage inside of myself. You very much resonate with the material – and get annoyed sometimes when things aren’t going right or it won’t dry and you don’t know why. Sometimes it takes two or three days, sometimes a week. It has its secrets. But that’s also what makes it so fascinating.

You learnt and perfected the urushi technique in Barcelona. How closely do you stick to the traditions and where have you moved away from them?

MS: Tradition plays a role for me in terms of the technique, i.e. the development of the lacquered object. This technique has proven itself over thousands of years and there is no improving on it. What I have changed is the manner in which I process the lacquer. For example, I don’t use charcoal for the grinding, as was the case in the past. Instead, I use wet sandpaper. And I don’t apply the filler with a carved wooden spatula, I use my finger – that’s the best spatula in the world! Essentially, I have avoided adopting the Japanese tradition from the outset, including when designing my objects. I am European and if I tried to copy Japanese art, it would only be a cheap copy. I always think about what object will set the lacquer off particularly well.

It is important to me to find forms which will still be perceived as beautiful in 50 or 100 years’ time. My goal is for the lacquer and form to enter into perfect harmony with one another. The shine and reflections on rounded forms are set off particularly well – so in that sense, the LAMY dialog 3 was perfect.

What was the biggest challenge for you with the LAMY dialog 3?

MS: The biggest difficulty was actually breaking away from old ideas. You have hundreds of images in your head of fountain pens coated in urushi, made by others – and the greatest task was to rid my head of these images or rather to switch off from them. And then it finally came to me after I had left everything alone for four weeks and thought that I wouldn’t be able to come up with anything. It was at a moment when I actually had no suitable blanks [editor’s note: body blank] – only blanks with a line engraved on them which I couldn’t use. So I carved them out and brushed along the length of the fountain pen. I can’t say exactly how I came to apply the grinding horizontally across the blanks too ... I would say it was an intuition. Something like that emerges or not, you can’t claim it. The urushi gods were merciful once again. And that’s how autumn, the first model, came about.

No layer is insignificant. Every layer has to be perfect.

Classic urushi only features in the colours black and red. For the autumn model, Manfred Schmid chose a transparent lacquer which emits an amber-like tone when applied in layers.

You have not used a classic black lacquer for autumn but rather a transparent lacquer. How did you come up with this idea?

MS: When the call from Lamy arrived, I was at a point where I was actually done with black lacquer. I had been ‘seeing black’ for 20 years and wanted to set off in search of something new and bring some colour into my life. I was interested in the so-called transparent lacquer. I say ‘so-called’ because it is translucent but not colourless. When applied correctly, it is amber-like in colour and reminds me of images from my childhood. At that time, we had a blind and when the street lamp beamed its light into my room, everything turned a wonderful golden-brown. The transparent lacquer is actually not used in Japan, at least not as a sole surface but rather as a kind of sealant. I applied this lacquer over the texture which I had previously ground into the fountain pen. The effect was very exciting: the texture is not covered up and actually radiates out from deep beneath the lacquer.

Once the collaboration with Lamy came about, you had moved away from classic black lacquering. Was there anything about your work on the LAMY dialog 3 which changed your perspective on urushi?

MS: Yes, definitely. Over decades of working with black lacquer, I have developed an astute eye for perfection. Through the collaboration with Lamy and exchanges with Mr Achenbach, I have actually realised that I sometimes see things as errors which he perceives as aesthetic. And that was actually the path I wanted to go down: moving away from black lacquer towards more vibrancy. It can be a long process to change one’s perspective and become more open again – for the beginner’s spirit, as they say in Zen.

Because the drawback of handwriting is also its real strength – the lack of speed, which these days is a rare luxury. Writing by hand has a meditative component.

As you say, autumn came about by change or through a kind of intuition. What was the inspiration behind spring and winter?

MS: There too, the idea came to me by chance. I was working on a large stainless steel bowl using the autumn technique mentioned previously and was again obsessed with perfection. I had already applied the first

layer 14 times and wiped it off again because it wasn’t even. I had tormented myself over it for two or three months and was so despairing that I could happily have thrown the bowl out of the window. When I reached the point of wanting to wipe off the final layer yet again and dunked my cloth in alcohol, some of it dripped into the bowl. I saw it and thought: wow, that looks great! So I took a fountain pen and began to experiment right away.

How is the effect created exactly?

MS: I dip the brush in alcohol and shake it off so that lots of small droplets are sprinkled on the fountain pen. This breaks down the surface tension of the lacquer and creates a special structure, as featured on the spring and winter models. The result is different every time. I could never recreate the exact same fountain pen – each one is completely unique.

A special brush is used to apply the urushi lacquer. The brush is made from human Asian hair and has a particularly smooth structure.